Model Selection#

In neurocognitive psychology, we often collect huge amounts of data — sometimes thousands of measurements from different brain regions or many behavioral scores. Having more information can, in theory, help us make better predictions, but it also brings risks: too many variables can make analyses infeasible, lead to false discoveries, or cause models to learn noise instead of real effects.

The large p issue#

Big data refers to large data sets with many predictors which often cannot be processed or analyzed using traditional data processing techniques. For our prediction models, this brings some issues:

While the linear model can in theory still be used for such data, the ordinary least squares fit becomes infeasible, especially when p > n

The large amount of features reduce interpretability

This is where linear model selection becomes essential, offering techniques to refine our models and extract meaningful insights from high-dimensional data.

Today’s data: Hitters#

For practical demonstration, we will use the Hitters dataset. This dataset provides Major League Baseball Data from the 1986 and 1987 seasons. It contains 322 observations of major league players on 20 variables (so it’s not big data, but we can pretend it is). The Research aim is to predict a baseball player’s salary on the basis of various predictors associated with the performance in the previous year. You can check its contents here: https://islp.readthedocs.io/en/latest/datasets/Hitters.html

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Get the data

hitters = sm.datasets.get_rdataset("Hitters", "ISLR").data

For computational reasons, we will not include all predictors but only a smaller subset:

# Keep a total of 10 variables - the target ´Salary´ and 9 features.

hitters_subset = hitters[["Salary", "CHits", "CAtBat", "CRuns", "CWalks", "Assists", "Hits", "HmRun", "Years", "Errors"]].copy()

# Remove rows with missing vlaues

hitters_subset.dropna(inplace=True)

hitters_subset.head()

| Salary | CHits | CAtBat | CRuns | CWalks | Assists | Hits | HmRun | Years | Errors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rownames | ||||||||||

| -Alan Ashby | 475.0 | 835 | 3449 | 321 | 375 | 43 | 81 | 7 | 14 | 10 |

| -Alvin Davis | 480.0 | 457 | 1624 | 224 | 263 | 82 | 130 | 18 | 3 | 14 |

| -Andre Dawson | 500.0 | 1575 | 5628 | 828 | 354 | 11 | 141 | 20 | 11 | 3 |

| -Andres Galarraga | 91.5 | 101 | 396 | 48 | 33 | 40 | 87 | 10 | 2 | 4 |

| -Alfredo Griffin | 750.0 | 1133 | 4408 | 501 | 194 | 421 | 169 | 4 | 11 | 25 |

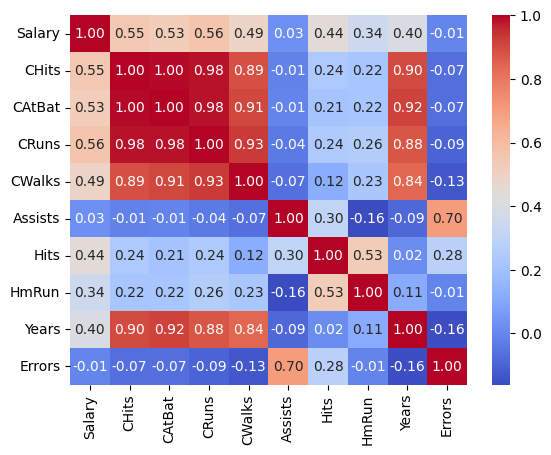

Let’s also take a look at the correlation matrix to check for potential multicollinearity, which can affect the stability of linear regression models.

import seaborn as sns

sns.heatmap(hitters_subset.corr(), annot=True, cmap="coolwarm", fmt=".2f");

The heatmap reveals strong correlations between several predictors:

CHitsandCAtBatshow a correlation of 1,CHitsandCRunshave a very strong correlation of 0.98,

We thus remove two of the correlated features:

features_drop = ["CRuns", "CAtBat"]

hitters_subset = hitters_subset.drop(columns=features_drop)

Handling big data in linear models#

Handling big data

To handle large datasets efficiently in linear modeling, we will introduce three methods:

Subset Selection

Dimensionality Reduction

Regularization / Shrinkage

Subset Selection#

In subset selection we identify a subset of p predictos that are truly related to the outcome. The model get fitted using least squares on the reduces set of variables.

How do we determine which variables are relevant?!

Best Subset Selection#

We will start with performing Best Subset Selection (also called exhaustive search) as implemented in the mlxtend package. It has great documentation, e.g. for the exhaustive search. In short, this approach is a brute-force evaluation of feature subsets. A specific performance metric (e.g. MSE, R², or accuracy) is optimized given an arbitrary regressor or classifier. For example, if we have 4 features, the algorithm will evaluate all 15 possible combinations of features.

Before we start the subset selection, we first define the target and the features:

import numpy as np

y = hitters_subset["Salary"]

X = hitters_subset.drop("Salary", axis=1)

We first split our data into training and test dataset. Although the selection function uses cross-validation to identify the best subset of predictors (Step 3), this evaluation is done during the selection process and can still overfit to the data. To fairly assess how the final model performs on new data, we split off a test set and use it only after feature selection is complete.

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=42)

Purpose |

What is it for? |

When? |

|---|---|---|

Cross Validation in selection function |

Helps choose the best subset of features |

During selection |

Test Set Evaluation |

Checks how well the final model performs |

After selection |

We then run Best Subset Selection on the training data:

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from mlxtend.feature_selection import ExhaustiveFeatureSelector

efs = ExhaustiveFeatureSelector(

estimator=LinearRegression(),

min_features=1,

max_features=X_train.shape[1],

scoring='r2',

cv=5,

print_progress=False)

efs.fit(X_train, y_train)

print('Best R²: %.2f' % efs.best_score_)

print('Best subset (indices):', efs.best_idx_)

print('Best subset (corresponding names):', efs.best_feature_names_)

Best R²: 0.41

Best subset (indices): (1, 3, 4)

Best subset (corresponding names): ('CWalks', 'Hits', 'HmRun')

If you are interested in the details, they are stored in the metric dictionary:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame.from_dict(efs.get_metric_dict()).T

df.sort_values('avg_score', inplace=True, ascending=False)

df

| feature_idx | cv_scores | avg_score | feature_names | ci_bound | std_dev | std_err | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47 | (1, 3, 4) | [0.38067374180608526, 0.463839312906159, 0.505... | 0.412539 | (CWalks, Hits, HmRun) | 0.100218 | 0.077973 | 0.038987 |

| 90 | (1, 3, 4, 6) | [0.3878486031208028, 0.4634739461791568, 0.493... | 0.408445 | (CWalks, Hits, HmRun, Errors) | 0.094497 | 0.073522 | 0.036761 |

| 83 | (1, 2, 3, 4) | [0.3813017586747449, 0.4658246874129488, 0.506... | 0.404694 | (CWalks, Assists, Hits, HmRun) | 0.098463 | 0.076607 | 0.038304 |

| 89 | (1, 3, 4, 5) | [0.33058568684405754, 0.46099452778892, 0.5147... | 0.403253 | (CWalks, Hits, HmRun, Years) | 0.105549 | 0.082121 | 0.041061 |

| 114 | (1, 2, 3, 4, 6) | [0.3751200780670817, 0.4651398463048052, 0.496... | 0.401198 | (CWalks, Assists, Hits, HmRun, Errors) | 0.095867 | 0.074588 | 0.037294 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 58 | (2, 5, 6) | [0.14956857373046695, 0.13751233647954653, 0.1... | 0.122419 | (Assists, Years, Errors) | 0.120381 | 0.093661 | 0.04683 |

| 5 | (5,) | [0.14935846878458914, 0.1343083510706763, 0.12... | 0.122124 | (Years,) | 0.135551 | 0.105464 | 0.052732 |

| 2 | (2,) | [-0.0025851222923383155, -0.007245558244625583... | -0.040331 | (Assists,) | 0.04707 | 0.036622 | 0.018311 |

| 6 | (6,) | [-0.02226936534097579, -0.006949819455392525, ... | -0.051379 | (Errors,) | 0.045878 | 0.035695 | 0.017847 |

| 21 | (2, 6) | [-0.04083051774641855, -0.007183353236134726, ... | -0.057133 | (Assists, Errors) | 0.042413 | 0.032998 | 0.016499 |

127 rows × 7 columns

Forward Stepwise Selection#

Forward Stepwise Selection is a greedy feature‐selection method that starts with no features and, at each step, adds the single feature whose inclusion most improves the model’s performance. This “add the best remaining feature” is repeated until a desired number of features is reached, at which point the algorithm stops and returns the best subset.

An important parameter is k_features, which determines the number of features to select. We can, pass an integer (must be less than the total number of available features), a tuple (the algorithm will then evaluate all subset sizes between the min and max value), or one of two string options ("best", or "parsimonious"). Please refer to the documentation for further details.

from mlxtend.feature_selection import SequentialFeatureSelector

sfs_forward = SequentialFeatureSelector(

estimator=LinearRegression(),

k_features=(1, X_train.shape[1]),

forward=True,

scoring='r2',

cv=5,

verbose=0)

sfs_forward.fit(X_train, y_train)

print(f">> Forward SFS:")

print(f" Best CV R² : {sfs_forward.k_score_:.3f}")

print(f" Optimal # feats : {len(sfs_forward.k_feature_idx_)}")

print(f" Feature indices : {sfs_forward.k_feature_idx_}")

print(f" Feature names : {sfs_forward.k_feature_names_}")

>> Forward SFS:

Best CV R² : 0.413

Optimal # feats : 3

Feature indices : (1, 3, 4)

Feature names : ('CWalks', 'Hits', 'HmRun')

You can see we ended up with the same three predictors as in best subset selection: CWalks, Hits, HmRun. However, this is not necessarily always the case — best subset and stepwise selection can, and often do, lead to different results. In our case we only had a small number of predictors, which makes it more likely to end up with the same subset.

Backward Stepwise Selection#

Backward Stepwise Selection begins with the full feature set and, at each step, removes the single feature whose exclusion most improves (or least harms) model performance. We keep repeating this “remove the worst feature” step until only the desired number of features remains, and then the algorithm returns that reduced subset:

sfs_backward = SequentialFeatureSelector(

estimator=LinearRegression(),

k_features=(1, X_train.shape[1]),

forward=False,

floating=False,

scoring='r2',

cv=5,

verbose=0)

sfs_backward.fit(X_train, y_train)

print(f"<< Backward SFS:")

print(f" Best CV R² : {sfs_backward.k_score_:.3f}")

print(f" Optimal # feats : {len(sfs_backward.k_feature_idx_)}")

print(f" Feature indices : {sfs_backward.k_feature_idx_}")

print(f" Feature names : {sfs_backward.k_feature_names_}")

<< Backward SFS:

Best CV R² : 0.413

Optimal # feats : 3

Feature indices : (1, 3, 4)

Feature names : ('CWalks', 'Hits', 'HmRun')

Subset Selection Summary#

Best Subset Selection |

Forward Stepwise Selection |

Backward Stepwise Selection |

|---|---|---|

+ will find the best model |

- not guaranteed to find best model |

- not guaranteed to find best model |

- may overfit with large p |

+ possible to use when p is very large |

+ possible to use when p is very large, given p<n |

- computationally very expensive |

+ computationally less demanding |

+ computationally less demanding |

What next?#

Once we have identified the features that are relevant for predicting the outcome, let`s evaluate the model performance and estimate true test error with the thee predictors identified by Best Subset Selection and Forward Stepwise Seletion.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error, r2_score

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

selected_features = list(sfs_backward.k_feature_names_)

# Subset the data

X_train_subset = X_train[selected_features]

X_test_subset = X_test[selected_features]

# Fit the model

model = LinearRegression()

model.fit(X_train_subset, y_train)

# Get predictions anf performance

y_pred = model.predict(X_test_subset)

mse_test = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred)

rmse_test = np.sqrt(mse_test)

r2_test = r2_score(y_test, y_pred)

print(f"Test MSE: {mse_test:.2f}")

print(f"Test RMSE: {rmse_test:.2f}")

print(f"Test R²: {r2_test:.4f}")

Test MSE: 182321.00

Test RMSE: 426.99

Test R²: 0.2492

So in sum:

On average, our predictions deviate from the actual salary by about 426 thousand dollars.

Our model explains ~25% of the variance in salary.

Regularization and Dimensionality Reduction#

As mentioned before, regularization and dimensionality reduction are two other measures of dealing with large numbers of predictors. Regularization techniques will be introduced in the next session, and dimensionality reduction will be introduced in the Principal Component Analysis session.