Support Vector Machines#

After a brief excursion into generative models such as LDA & QDA or Naïve Bayes, we will now again discuss a discriminative family of models: Support Vector Machines (SVM). SVMs are powerful supervised learning models used for classification and regression tasks. When used for classification, they are called Support Vector Classifiers (SVC).

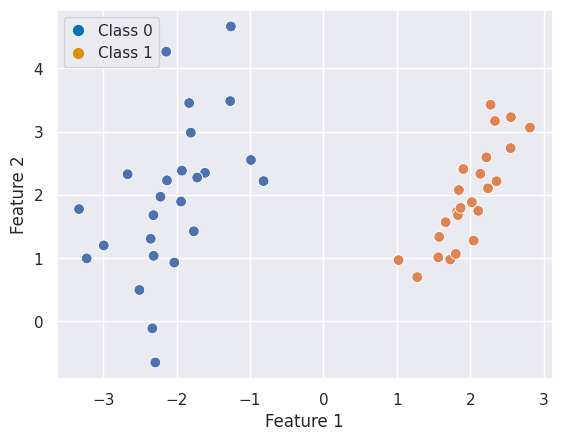

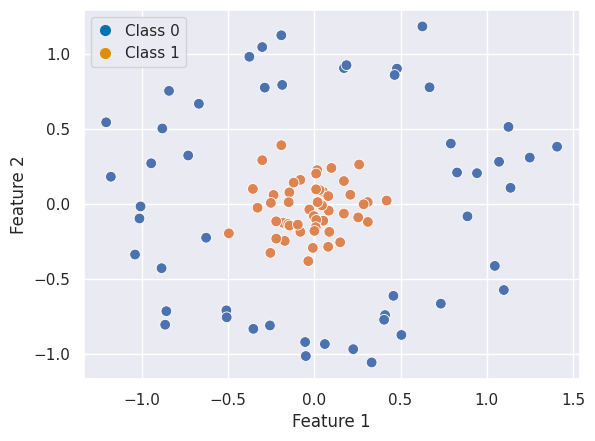

Let’s consider some simulated classification data:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from scipy import stats

from matplotlib.lines import Line2D

from sklearn.datasets import make_classification

sns.set_theme(style="darkgrid")

X, y = make_classification(n_samples=50, n_features=2, n_informative=2, n_redundant=0,

n_clusters_per_class=1, class_sep=2.0, random_state=0)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

sns.scatterplot(x=X[:, 0], y=X[:, 1], hue=y, s=60, ax=ax)

ax.set(xlabel="Feature 1", ylabel="Feature 2")

# Custom legend

legend_elements = [

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 0', markerfacecolor="#0173B2", markeredgecolor='None'),

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 1', markerfacecolor="#DE8F05", markeredgecolor='None')]

ax.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc="upper left", handlelength=1);

Solution

There are infinite ways to separate the two classes because you can find an infinte amount of lines which perfectly separate them.

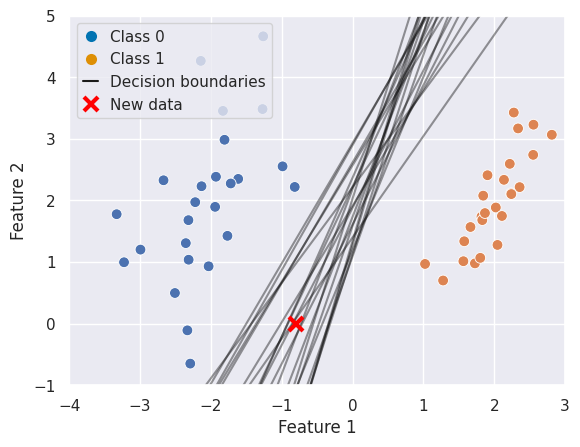

If we visualise this and add a new data point for classification a potential issue becomes apparent. For some models, this data point would fall into Class 0 and for others into Class 1:

Support Vector Classifiers (SVC)#

So evidently, we can’t just be satisfied with having an infinite amount of possible solutions we need to come up with a more justifiable one. If you remember, we already did so for linear regression: there, the least squares method chose the line that minimised the total squared distance between predictions and true values.

Support Vector Classifiers have a slightly different method. As Robert Tibshirani put it, they are

An approach to the classification problem in a way computer scientists would approach it.

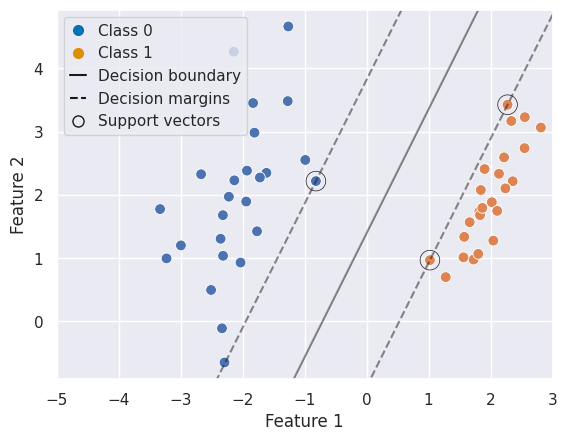

Rather than minimising a squared error, they aim to find the hyperplane that maximises the margin — the distance between the separating hyperplane and the closest data points from each class. The idea is that by maximising this margin, we obtain a decision boundary that is both robust and generalisable.

Hyperplane: A decision boundary that separates classes. In p dimensions, it is a p−1 dimensional subspace, given by the equation: \(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_p X_p = 0\). So in the case of two predictors the hyperplane is one dimensional (a line).

Separating Hyperplane: A hyperplane that correctly separates the data by class label.

Margin: The (perpendicular) distance between the hyperplane and the closest training points. A maximal margin classifier chooses the hyperplane that maximises this margin.

Support Vectors: Observations closest to the decision boundary. They define the margin and the classifier.

Soft Margin: A method used when the data is not linearly separable. Allows some observations to violate the margin. Controlled via the hyperparameter \(C\).

Kernel Trick: Implicitly maps data into a higher-dimensional space to make it linearly separable using functions like polynomial or RBF (Gaussian) kernels.

To formalise this intuition, SVCs look for the maximum margin classifier — a hyperplane that not only separates the classes but does so with the greatest possible distance to the closest training samples. These closest samples are known as support vectors, and they uniquely determine the position of the hyperplane. All other samples can be moved without changing the decision boundary, making SVCs especially robust to outliers away from the margin.

Using SVCs#

As you learned in the lecture, SVCs are considered to be one of the best “out of the box” classifiers and can be used in many scenarios. This includes:

When the number of features is large relative to the number of samples

When classes are not linearly separable

When a robust and generalisable classifier is needed

If the data is not perfectly separable (either because the classes overlap, or the classes are not linearly separable) SVCs become creative in two ways

“Soften” what is meant by separating the classes and allow for errors

Map feature space into a higher dimension (kernel trick)

Example 1: Linear Classification#

Fitting a SVC is straigthforward:

from sklearn.svm import SVC

clf = SVC(kernel='linear')

clf.fit(X, y);

With a little helper function we can visualize the decision function and supports:

Example 2: Nonlinear Classification#

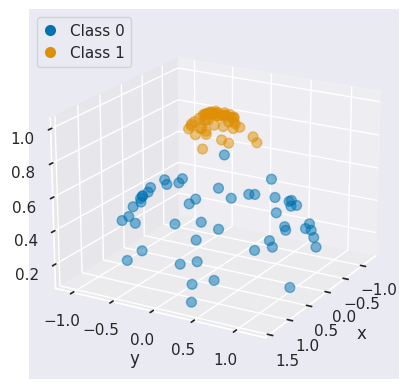

Let’s consider different data, which is not linearly separable:

from sklearn.datasets import make_circles

X, y = make_circles(100, factor=.1, noise=.15)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

sns.scatterplot(x=X[:, 0], y=X[:, 1], hue=y, s=60, ax=ax)

ax.set(xlabel="Feature 1", ylabel="Feature 2")

# Custom legend

legend_elements = [

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 0', markerfacecolor="#0173B2", markeredgecolor='None'),

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 1', markerfacecolor="#DE8F05", markeredgecolor='None')]

ax.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc="upper left", handlelength=1);

In that case, non-linear SVC can be applied. For example, a simple projection would be a radial basis function centered on the middle clump. As you can see, the data becomes linearly separable in three dimensions:

from mpl_toolkits import mplot3d

# Apply radial basis function to the feature space

r = np.exp(-(X ** 2).sum(1))

# Plot features in 3D

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(projection='3d')

colors = np.array(["#0173B2", "#DE8F05"])[y] # colors for each class

ax.scatter(X[:, 0], X[:, 1], r, c=colors, s=50, alpha=0.5, edgecolors=colors)

ax.view_init(elev=20, azim=30)

ax.set(xlabel='x', ylabel='y', zlabel='r');

# Custom egend

legend_elements = [

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 0', markerfacecolor="#0173B2", markeredgecolor='None'),

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 1', markerfacecolor="#DE8F05", markeredgecolor='None')]

ax.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc="upper left", handlelength=1);

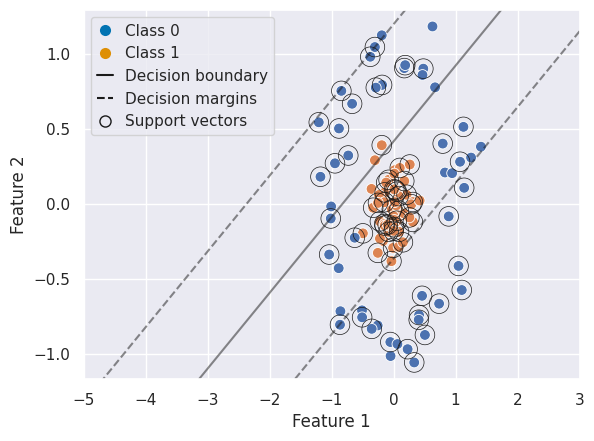

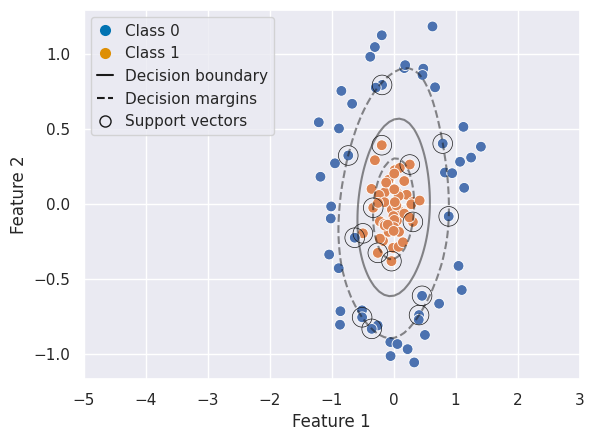

We can create a similar plot as above, first with a linear SVC and second with a RBF SVC to visualize the decision boundary, margins, and support vectors:

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3)

# Linear SVC

clf_lin = SVC(kernel='linear')

clf_lin.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = clf_lin.predict(X_test)

print("Linear SVC classification report:\n", classification_report(y_test, y_pred))

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

sns.scatterplot(x=X[:, 0], y=X[:, 1], hue=y, s=60, ax=ax)

ax.set(xlabel="Feature 1", ylabel="Feature 2", xlim=(-5,3))

plot_svc_decision_function(clf_lin, ax=ax)

# Custom legend

legend_elements = [

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 0', markerfacecolor="#0173B2", markeredgecolor='None'),

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 1', markerfacecolor="#DE8F05", markeredgecolor='None'),

Line2D([0], [0], color='k', linestyle='-', label='Decision boundary'),

Line2D([0], [0], color='k', linestyle='--', label='Decision margins'),

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', color='k', markersize=8, label='Support vectors', markerfacecolor='None', linestyle='None')]

ax.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc="upper left", handlelength=1);

Linear SVC classification report:

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.83 0.33 0.48 15

1 0.58 0.93 0.72 15

accuracy 0.63 30

macro avg 0.71 0.63 0.60 30

weighted avg 0.71 0.63 0.60 30

# RBF SVC

clf_rbf = SVC(kernel='rbf')

clf_rbf.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = clf_rbf.predict(X_test)

print("RBF SVC classification report:\n", classification_report(y_test, y_pred))

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

sns.scatterplot(x=X[:, 0], y=X[:, 1], hue=y, s=60, ax=ax)

ax.set(xlabel="Feature 1", ylabel="Feature 2", xlim=(-5,3))

plot_svc_decision_function(clf_rbf, ax=ax)

# Custom legend

legend_elements = [

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 0', markerfacecolor="#0173B2", markeredgecolor='None'),

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 1', markerfacecolor="#DE8F05", markeredgecolor='None'),

Line2D([0], [0], color='k', linestyle='-', label='Decision boundary'),

Line2D([0], [0], color='k', linestyle='--', label='Decision margins'),

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', color='k', markersize=8, label='Support vectors', markerfacecolor='None', linestyle='None')]

ax.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc="upper left", handlelength=1);

RBF SVC classification report:

precision recall f1-score support

0 1.00 1.00 1.00 15

1 1.00 1.00 1.00 15

accuracy 1.00 30

macro avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 30

weighted avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 30

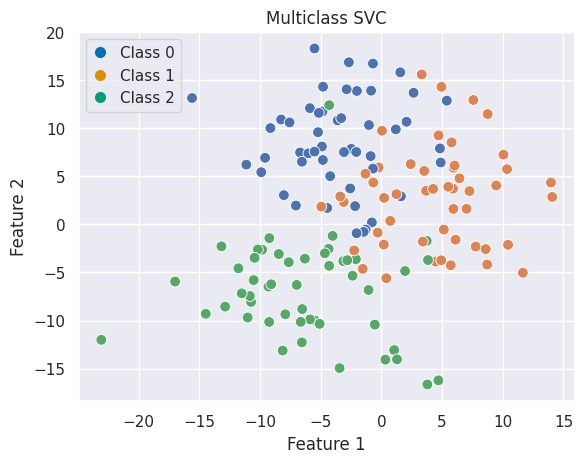

Multiclass Classification#

SVCs are inherently binary classifiers but can be extended:

One-vs-One: \(\binom{K}{2}\) classifiers for each pair of classes.

One-vs-All: K classifiers, each comparing one class against the rest.

In sklearn you can, for example, use the ovo decision function for one-vs-one classification:

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

# Generate data

X, y = make_blobs(n_samples=150, centers=3, random_state=42, cluster_std=5)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, stratify=y, random_state=42)

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

sns.scatterplot(x=X[:, 0], y=X[:, 1], hue=y, palette='deep', ax=ax, s=60)

ax.set(xlabel="Feature 1", ylabel="Feature 2", title="Multiclass SVC")

legend_elements = [

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 0', markerfacecolor="#0173B2", markeredgecolor='None'),

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 1', markerfacecolor="#DE8F05", markeredgecolor='None'),

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', linestyle='None', markersize=8, label='Class 2', markerfacecolor="#029E73", markeredgecolor='None')]

ax.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc="upper left", handlelength=1);

plt.show()

# Multiclass prediciton

clf = SVC(kernel='rbf', decision_function_shape='ovo')

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = clf.predict(X_test)

print("Multiclass classification report:\n", classification_report(y_test, y_pred))

Multiclass classification report:

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.78 0.58 0.67 12

1 0.65 0.85 0.73 13

2 1.00 0.92 0.96 13

accuracy 0.79 38

macro avg 0.81 0.78 0.79 38

weighted avg 0.81 0.79 0.79 38

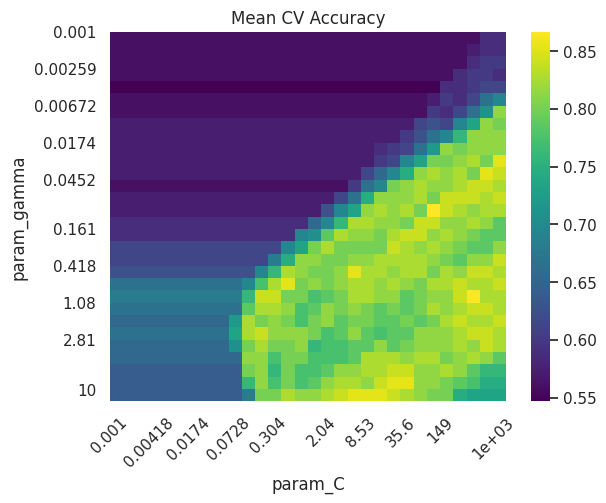

Choosing Hyperparameters#

SVCs have a few hyperparameters. Please have a look at the documentation for a more in-depth overview. For the SVC used in the previous examples, the most important ones are:

C: Regularisation parameter; trade-off between margin width and classification error.kernel:'linear','poly','rbf','sigmoid', or custom.gamma: Kernel coefficient (for RBF, polynomial, and sigmoid kernels)

Note

In sklearn (and usually also MATLAB and R) C behaves inversely to what you were shown in the lecture. Small values of C will result in a wider margin, at the cost of misclassifications (high bias, low variance). Large values of C will give you a smaller margin and fit the training data more tightly (low bias, higher variance).

As always, hyperparameters should be tuned using cross-validation to balance bias and variance. It often makes sense to use a grid search or related strategies to find the optimal solution:

Best parameters: {'C': np.float64(385.6620421163472), 'gamma': np.float64(0.7880462815669912), 'kernel': 'rbf'}

Best cross-validation score: 0.8666666666666668

Test set score: 0.88

Summary

Support Vector Classifiers are a robust and versatile tool for classification tasks

The key ideas are rooted in geometry - finding the optimal hyperplane that separates data with maximum margin

With the use of kernels, SVCs extend effectively to non-linear decision boundaries

Multiclass classification can be done in a one-vs-one or one-vs-all approach

Even though we did not do so here, it is often useful to scale the predictors (see exercise)

Additional References#

For more information and a cool example for facial recognition, you can have look at the Python Data Science Handbook notebook.